When you hear the term “majority culture,” what is the first thing that comes to mind? What thoughts or feelings arise within you? What images or memories of the past resurface?

The history of ethnic minorities in North America is filled with pain from both the reality of living on the margins of society as immigrants and the wounds of injustice from those in power. This article is written by five members of ethnic minority cultures who have wrestled with how to minister and lead through that pain in healthy ways.

Adrian and Jennifer minister with Epic Movement (Asian American ministry), Kristy with Destino Movement (Latino or Hispanic American ministry), and Donnie and Renee with Nations Movement (Native American ministry) – which are all ethnic ministries in a predominantly Caucasian ministry organization, Cru Global (formerly known as Campus Crusade for Christ).

A few months ago, some of our Caucasian colleagues released an article called “Five Majority Culture Postures Towards Ethnic Minority Ministry.” It explained a “posture” as an approach involving not only the mind, but also the heart and attitude. Five postures were outlined: (1) Unfamiliar and Unaware (2) Duty or Obligation (3) Charity (4) Unity as Togetherness (5) Advocacy in Partnership.

Whether we know it or not, each member of an ethnic minority culture also has a posture towards the majority culture. Likewise, this influences what we value, how we make decisions, and how we treat others. As we have served in our ethnic minority contexts for the past few years, we have noticed a lack of awareness and dialogue about this.

Much attention and energy has been focused on how we have been treated. But in this process we have often failed to recognize the power and responsibility that God has entrusted to us as His children. In waiting for others to change or initiate with us, we have sometimes missed what God wants to do in our hearts and lives. Whether we live on the margins or in positions of power, we all play a part in God’s story. He calls us all to examine our postures as we act and lead.

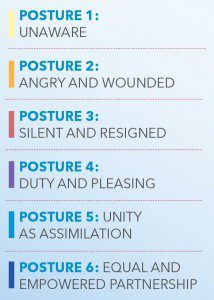

As we have ministered, we have consistently experienced and identified six postures towards the majority culture. They are: (1) Unaware (2) Angry and Wounded (3) Silent and Resigned (4) Duty and Pleasing (5) Unity as Assimilation (6) Equal and Empowered Partnership.

As you read, you may not identify with one over another. Perhaps aspects of two or three will best represent your heart and attitude towards the majority culture. Our hope is that you pay attention to what this surfaces within you and make an honest assessment of your own posture. We pray that you’ll take the time to reflect on what God might be encouraging you to consider in your own development and leadership.

DISCLAIMERS:

- Postures are not linear but complex. One might experience many, even within the same experience, over the course of a lifetime.

- This article is not intended as a condemnation of any of the postures. All of the authors have experienced them and continue to navigate them by God’s grace.

- We don’t claim to represent the entire ethnic minority experience. We hope this article provides a platform for insights and stories that are missing to add to an ongoing dialogue and narrative.

Posture # 1: Unaware

The first posture we have observed is best described as Unaware. Some ethnic minorities have formed or found communities where they are surrounded by those of their own culture. As a result, they have rarely been in situations where others have seen them as different or where they have felt like a minority; they feel “normal” because of what their context has defined as such. Thus, though they live and breathe their own culture, they may actually be quite unaware of the distinctiveness of their own ethnic background.

For others, perhaps they engage in multicultural contexts and relationships but are unaware because differences are not thought about or discussed openly. Either of these contexts can encourage the misperception that culture is non-existent or simply not important.

By God’s grace, we are all in different places on our journey of awareness and none of us has “fully arrived.” Maybe you wonder why it’s even important for a person to explore their culture and ask questions when they seem to be “fitting in” without any problems. Or maybe you are just beginning to understand the various family and cultural factors that have shaped you.

Regardless of where you are in your journey, consider what opportunities for growth and leadership that have been previously overlooked lie ahead for you and others!

As ethnic minorities, if we choose to stay in mono-cultural environments that don’t engage the majority culture we may spare ourselves the pains of marginalization, the confusion of feeling different, and the tension of “not fitting in.” However, in doing so, we will miss the fullest vision of who God has created us to be. We are able to more fully grasp our unique identity as we navigate the tension that comes from being with those different from ourselves.

Moreover, if we stay disengaged, we will hold back our unique values and stories from the body of Christ. There are new and rich pictures of your identity, family, history – and of God – that are waiting for you to learn and share!

If we choose to ignore cultural diversity and dynamics, we may also spare ourselves the discomfort and hard work of cross-cultural communication and partnership. However, in doing so we will miss redemptive opportunities that God is calling us to embrace. As ethnic minorities, we cannot wait for the majority culture to recognize differences or enter into our stories before we engage them.

How might God be calling you to initiate, both within your own culture and with the majority culture, as you help others begin to see differences as opportunities to grow and learn?

Growing up in Southern California, it was easy for me to find Asian American communities where I felt normal and at home. I attended a Chinese American church, but if you had closed your eyes, it would have been hard to know we worshipped any differently than others, since we never talked about culture. I noticed that both ethnic minorities and Caucasians were reluctant to talk about having a distinct culture. However, subconsciously they all gravitated towards those who were similar to them. Culture was important to them, but they didn’t know it. They didn’t know they were unaware, just like me. (Jennifer Pei)

Posture # 2: Angry and Wounded

The second posture that we have observed is best described as Angry and Wounded. The history of ethnic minorities in the United States is filled with wounds, many from years of oppression or injustice. Some of that pain is reinforced by a lack of apology or even acknowledgment of past wrongs or insensitive exhortations to “forget the past” and to “just move on.”

Still others may feel their present experiences are minimized from well-intentioned people who claim that “things are different now,” when racism and discrimination are sobering realities that continue to this day.

For many ethnic minorities whose wounds are so deeply personal, whether from their own lives or those of loved ones, this can build the foundation of a posture of anger towards the majority culture.

This can manifest itself in many different situations and to various degrees of intensity. Some choose to separate themselves or retaliate, seeing the majority culture itself as the enemy. Others maintain a high level of mistrust, finding it difficult to listen to (or share with) Caucasians without some suspicion of motives.

Anger can be overt and direct but it can also manifest itself in more subtle ways, especially in cultures where expressing anger is difficult or even considered sinful. Maybe you feel a surge of emotion when you see cultural stereotypes in the media or you respond with sarcasm when your co-worker remarks about your skill at speaking English. Maybe you find yourself acting defensively or even with arrogance when there’s a display of cultural ignorance or insensitivity.

We believe that anger may be, at times, not bad in itself – at times, anger has its foundation in the very attributes of God’s holiness and justice. At such times, one ought not to devalue feelings of anger since they originate from a desire for righteousness and experiences that have violated that.

However, when anger becomes part of the motivation in a ministry context, it can perpetuate the very mistreatment it stands against. Ministering out of anger can shut off dialogue and relationships and discourage those who sincerely want or need to learn. It can separate us from the body of Christ and all the ways that we need to learn from Jesus through those who are not like us.

If you find anger consistently surfacing within you in ministry contexts, consider what or who might trigger those feelings, and why. Consider its impact on your relationships and whether it has moved you towards, or away from, others. Has it led to greater honesty and accountability or to silence and avoidance?

As we learn to identify our anger and wounds and bring them to God and our community in a healthy manner, we can find great healing. God wants us to be part of His healing and sanctification process in community in a way that does not trivialize pain but works through it to build greater strength and character. In addition, as we share our stories of pain to the majority culture, we can model both truth and grace without sacrificing one to the other.

We can communicate with an honesty that does not minimize the past or present while leading towards healing and restoration as we learn to extend grace as Christ did.

Anger can sometimes stem from experiences of betrayal. In 1868, American settlers violated the Treaty of Fort Laramie, and seized land that belonged to the Native Lakota people. More than a century later, a Supreme Court ruling offered the Lakota over $150 million for this wrong, but the Natives refused to accept payment. They felt betrayed by the loss of their land, but also their dignity. Many settlers were attempting to “civilize” them, requiring minors to have an “English education” at mission buildings.

Many Native Americans today have attended similar boarding schools, where they were discouraged from speaking their native language, and forced to cut their hair – which is sacred to them. I remember hearing stories of relatives and friends who were abused at the hands of teachers and even priests. Because of these betrayals, many do not trust churches, and will not listen. This is our challenge, as Natives who remember and feel the pain of our people in all of its agony, and as Christians who work towards redemption. (Donnie Begay)

A few years ago, I was talking to one of my Caucasian friends who has a heart for serving in urban communities. As she told me of her passion, she stated, “most black kids can’t read.” At first, I reacted strongly, as this brought back painful memories of similar statements, and the (often unintentional) condescension behind them. However, because I knew my friend and her good intentions, I decided to have an open and honest conversation with her about how her comment made me feel. She apologized, and asked me for further insight and wisdom, for her own learning and understanding. Although I was tempted to withdraw when I first heard her statement, my friendship with her kept me engaged, and led to a deeper understanding for us both. (Patrice Holmes)

Posture # 3: Silent and Resigned

The third posture that we have observed is best described as Silent and Resigned. Although this often is caused by wounds described in the previous posture, the difference lies in the response. Those in this posture don’t see the majority culture as an enemy that one must fight but as an overwhelming force that cannot be resisted.

As mentioned in the previous posture, some minority cultures discourage the expression of emotions or sharing their pains beyond the tightest circle of family and friends. Thus, instead of expressing anger outwardly, many minorities turn it inward upon themselves. Instead of being silenced by others, they silence themselves in despair. Rather than banding together with others to form a common voice, they resign themselves to isolation or victimhood because they feel that nobody sees or hears them. This can lead to depression and even high rates of suicide in some cultures.

This perception of never having a place or voice in society, often rooted in painful experiences of marginalization, usually stems from a false belief that one has nothing valuable to offer. So a person, and those he or she may be leading, stays on the margins.

Sometimes we may assume this posture in subtle ways, without fully realizing it. Maybe we find ourselves constantly questioning or second guessing the thoughts in our heads while we sit in meetings. Maybe we tend to retreat or withdraw when faced with conflict or opposition. Maybe we find it difficult to receive praise or recognition because our self-doubt runs so deep.

But we serve a God who sees the invisible, hears the voiceless, and remembers those who have been forgotten. He teaches us to voice our pain to Him. He reminds us that we have worth and dignity because of who He created us to be, not because of the way society may perceive us. And as we lead out of this truth, God empowers us to lead even in contexts where we feel we have no voice!

Moreover, we don’t need to be seen before we can see others on the margins; we don’t need to be heard before we can hear the voiceless. We can advocate for others, even more so because we understand their pain. How can we empower others to live out of their unique beauty and dignity which we know has been hidden for too long?

Picture two people, if you will. A Japanese American woman who visits museums and schools, bringing books and pictures of Manzanar, a concentration camp in California. She speaks of the suffering, of all her relatives and friends who would say, Shikata ga nai, translated as “It can’t be helped.” But she also speaks of her Christian faith that gave her hope. She says, “I want to make sure people never forget. May my children and grandchildren always remember.”

Second, a Navajo man travels the world, meeting with tribes and speaking before churches and councils on behalf of Native Americans. He has a vision that every man and woman should have a voice in this country, though they live in remote hogans with no electricity, phone, or Internet. These are real people we know. God is looking for those who will not let their voice be drowned out nor silenced. He’s looking for advocates who will speak for those who cannot do so themselves. (Adrian Pei and Donnie Begay)

Posture # 4: Duty and Pleasing

The fourth posture can best be described as Duty and Pleasing. Unlike the previous two postures, this one is actively engaged, seeking to work with the majority culture. On the surface, this often appears as a healthy spirit of cooperation and partnership; of “being in this together” and “making it work.”

However, without an awareness or processing of power dynamics, ethnic minorities can often unknowingly find themselves in a paternalistic or dependent relationship with the majority culture instead of a truly empowering partnership.

Because the majority culture has been in a dominant position for so long, there’s a natural tendency for ethnic minorities to assume a role of duty or dependence in a cross-cultural leadership context. We are so used to not being in positions of power that our instincts are to defer to others, or step aside. Sometimes it’s a deference to wait for approval before making decisions or moving forward with leadership decisions. Or it’s a sense of duty or obligation to depend on the majority culture for direction, resources, or validation – because we want so badly to feel accepted.

We want to be clear – we believe that we should listen to, respect, and honor our leaders regardless of their ethnicity. We are not advocating separatism or disrespect in any way. But there is a world of difference between respect and deference. Honoring someone is not the same as being dependent on them.

As leaders ourselves, we don’t want to be in a paternalistic relationship with those we lead. We want them to grow as adults who are taking full ownership of their scope.

For ethnic minorities, it can be tempting to assume this posture for several reasons. First and foremost is a deep-seated belief that their culture is inferior to the majority culture. Some minorities consistently see negative portrayals or devaluing stereotypes of their culture in the media. Others have historically assumed “service” roles that are considered to be of “lower” status in society. All of this can create a deep sense of shame which can impact how minorities see their roles and worth in ministry contexts as well.

Another reason ethnic minorities may take a “pleasing” posture is that many immigrants saw themselves as visitors to the United States; this was not “their” country nor home.* (Note: This is not true for Native Americans, who are the only non-immigrants in North America. Many forget that the first American settlers were also immigrants, fleeing their homeland, and their arrival to the “New World” was as visitors to an already occupied land.) Their primary hope was for a better job and life for their families. As a result, they didn’t want to cause any problems and they taught their children based upon this philosophy. Thus, many minorities of today’s generation inherit a mentality to “not make waves” but go along with what the majority culture might deem as good or right.

This posture can be very subtle. We can’t imagine many would claim that it’s what they desire or are trying for. However, it is one of the most common and consistent relational patterns we have seen in ministry.

Do you ever find yourself seeking permission or approval from the majority culture for what you are doing or needing them to tell you what to do even if you don’t really need them to? Maybe you place your primary hope in decisions or statements made by your leaders. Or when they don’t get what they prefer or want maybe you change your stance or approach to appease them. When they disagree with your ideas maybe you are quick to give in.

If you find yourself identifying with aspects of this posture, consider what it might look like to stay engaged with, but not dependent on, your leaders. Consider how your ministry can lead authentically out of its culture without needing permission or validation from the majority culture. How might your leadership and culture even shape the future and direction of your greater ministry context?

“What is a Minority? Beyond Statistics, to Power and Status…” In recent years, many reports have come out about the fast rate at which ethnic minority populations are growing in the United States. The Census Bureau estimates that within a generation, over 50% of the population will no longer be Caucasian. CNN and the New York Times state that by then “minorities may be the U.S. majority.”

But it is crucial to understand that a numerical minority is not the same as a sociological minority. For years, women have comprised at least 50% of the United States’ total population and yet have struggled for equality. Even if ethnic minorities outnumber Caucasians in this country, they may very well be sociological minorities in regards to their social status, power, and privilege. Both minorities and the majority culture must deepen their understanding beyond statistics, if they are to minister in ways that model true equality.

Growing up as a Latina in the United States was difficult for me. In high school, I remember sitting with some Caucasian friends, as they casually commented about “the lazy Mexicans who were sitting drinking water under the shade, instead of working on their roof.” I don’t think it even crossed their minds that their offhand comment might be offensive to me. The community and media often portrayed that Latinos were inferior or a threat to society, and I began to feel shame about who I was.

More recently, I asked a group of Destino student leaders what their community could look like if Christ radically changed them. They responded, “Finally people would know that Latinos aren’t lazy or stupid, because God would be using us in big ways.” They weren’t letting stereotypes determine their worth or dignity, but had a vision for how God saw them. (Destino Kristy)

As a child, I distinctly remember when my father asked me to draw a picture of a girl. Without hesitation, I sketched the image of a Caucasian girl. There was no overt discrimination that caused this, but simply the internalization of what I understood to be the American cultural standard of beauty. Deep inside, I wished I could trade my Asian features for those of my Caucasian friends so that I could be accepted.

Now that I’m older, I still see ethnic minorities who unknowingly try to imitate the majority culture, whether in their hobbies, appearance (for instance, I see Asian American men who are ashamed of, and try to change their sometimes smaller body frames), communication styles, or approaches to leadership. It makes me wonder: how can we affirm the beauty in all of who we are, rather than changing ourselves to please others? (Jennifer Pei)

Posture # 5: Unity as Assimilation

The fifth posture is best described as Unity as Assimilation. As representatives of various ethnic minority groups, we desire as much as anyone to see true unity expressed and lived out. However, as the “Five Postures” article pointed out, efforts toward unity can often lead to uniformity which devalues uniqueness and differences. While the temptation for the majority culture is to keep things the same so they don’t have to face discomfort or adapt, the temptation for minority cultures is to conform (or assimilate) to the existing culture.

When many minorities enter a multiethnic church setting, they often encounter pressure to not discuss differences due to fear that this may lead to division in the body of Christ. Or sometimes, cultural conversation is discouraged because people feel it “waters down” the gospel. Silence about an issue does not necessarily mean neutrality, as some people may assume. This kind of silence is not due to unawareness but due to underlying beliefs about the meaning and value of culture and context.

Whether subtle or overt, many minorities respond to these pressures by thinking they must leave behind their culture to embrace a “new” and “superior” one in Christ. This creates a misleading – and potentially damaging – dichotomy between culture and faith. Without the proper awareness and maturity, minorities may associate (or even equate) “fallen-ness” with their ethnic identity and spiritual conversion with assimilation into the majority culture.

We acknowledge that unity is complex and that it needs to be discussed and pursued with thoughtfulness and care. Yet in the history of debates about the true meaning of contextualization and unity, we have noticed how little attention has been given to the concept of “loss.” As ethnic minority leaders, what of our family and culture’s story have we forsaken in pursuit of an immature vision of unity?

Yet we can bring these stories to enrich the body of Christ! As we begin to see diversity as adding depth to our theological and spiritual community rather than diluting it, we are freed to bring all of who we are to our ministry.

As we begin to value complexity rather than discourage it, we can lead as bridge-builders who help others to navigate the tension of multicultural settings.

We have noticed that unity in the Western church is very influenced by an individualistic mindset. People see themselves as distinct individuals, even if they don’t consider cultural distinctives. To be in community, each person must find it, and adapt to the culture. In our Native culture, we are simply born into the community of our families, and this is for life. You are part of a clan, and any debt or burden becomes the clan’s responsibility. When we are on the reservation, we don’t have to try to fit in or be unified – we are already tied to each other. But when we are off the reservation, it’s an entirely different story. (Renee Begay)

Posture # 6: Equal and Empowered Partnership and Moving Forward

If you’re a member of an ethnic minority culture, you have a story that has been largely untold in this country. You have a unique place in a history that has been largely incomplete of your values and leadership. There’s an incredible opportunity to shape the future of your cultural story and the way minorities relate to the majority culture as you embrace God’s calling to lead out of the unique beauty and dignity of your identity. It is a call to an equal and empowered partnership wherein minorities understand and embrace their God-given authority to define their own reality while still staying connected to the majority culture.

We use the words “equal” and “empowered” because our posture reveals how we see ourselves in relation to others. If we believe we are “above” another culture, we will talk and act as if they have nothing to teach or offer us. We won’t see our own need to learn and grow. Likewise, if we believe we are “below” another culture, we won’t see what we ourselves have to offer. In an equal partnership, both sides give and receive from one another because they see their need for each other.

If we as ethnic minorities believe we are equal to the majority culture, we will act in empowered, not dependent, ways. We will seek out opportunities to teach about our culture and history. We will not wait for others to initiate with us but we will bring our leadership to them.

True partnership holds both sides to the highest of standards. As we become empowered as minorities, God expects more – not less – from us.

This is a picture that the world may find difficult to understand. When you’ve lived most of your life on the margins of society and you are consistently silenced, it’s easy to believe that you are powerless. But this is simply not true.

The majority culture has status and privilege that we may never possess in this country. But as individuals made in the very image of God, we are entrusted with a power and responsibility far greater than we can imagine. We as ethnic minorities greatly underestimate this.

We have the power to bring stories to the light of truth or suppress them in the darkness of secrecy and shame. We have the power to embrace our cultural identity and lead others along the way and to advocate for those who cannot do so for themselves. We must not fail to recognize and steward this power!

We also have the power to wound or heal others by our words and actions. As minorities, we must remember that many in the majority culture are also on a journey filled with confusion and insecurity. They need our compassion and leadership as they grow in greater awareness of themselves, others, and God. As we lead as equals, we must treat them with grace and dignity even if we feel we have not received that ourselves.

At times this will involve difficult conversations and pain. As ethnic minority leaders, we may share perspectives that force the majority culture to honestly examine the broken parts of their culture and history. Similarly, as our friends and leaders in the majority culture enter into our stories, they may speak truth into areas of our culture that need redemption.

This process can cause both sides to feel discomfort, defensiveness, and insecurity. However, as equals, both sides must be willing to listen and learn from that. Our cross-cultural relationships need to be able to handle truth that leads to transformation with grace. And as we do this justly and with honor, we live out a picture of God’s body and coming kingdom.

Yet we don’t have to wait for heaven to experience this! As we ethnic minority leaders have embraced our God-given responsibility to lead, we have seen this vision lived out.

We have seen majority culture leaders with the humility to not only cross cultures but be led by minority leaders. These advocates believe so strongly in the value of other cultures within their ministry that they have let their own beliefs be shaped in the process. We have seen cross-cultural partnerships where majority and minority leaders have mutual respect, learning, and trust; where powerful alliances have formed out of the strength of two different but equally powerful voices.

We have seen empowered minority leaders emerge who are embracing their cultural identity, believing they have a unique voice at the highest levels of leadership. We have seen them influence and empower many in the majority culture. We have seen dignity restored to cultures that had been devalued and silenced as God has used them to influence change in His greater body and kingdom.

Can you picture this in your ministry or context? Can you imagine mutually uplifting and honoring relationships in which both sides care enough to not let the other stay dependent or disempowered? Can you picture relationships where differences are stewarded with justice, mercy, and humility and form the foundation for an even stronger alliance?

To What End?

As ethnic minorities, we cannot wait for the majority culture before we choose to live out a posture of equal and empowered partnership. We lead because of who God created us to be not out of reaction to how others may define us.

However, many barriers stand in the way of this vision whether it’s unawareness, anger, resignation, deference, feelings of inferiority, or fear of differences and change. Some of these are deep-seated and have roots in unprocessed wounds of past generations. Engaging our pain can be costly. Sometimes we feel it’s easier to not think or talk about it or to stay emotionally or relationally separate from the majority culture.

This is our challenge: how do we move forward when so much inside and outside of us is telling us to pull away? Moving forward does not mean forgetting or trivializing our past. It does not mean leaving the dreams and hopes of our families behind. It is not denying who we are or self-sacrificially putting ourselves into unhealthy or abusive relationships.

Moving forward means unapologetically bringing all of ourselves to our leadership and relationships and inviting the majority culture to do the same for our benefit. It means a willingness to dialogue with mutuality and respect through our differences and disagreements. It means a heart to learn and serve not because we feel inferior but because we see others as equally valued members of God’s creation.

We move forward with the integrity to stand firm in our God-given identity and the courage to extend grace where pain has been experienced. This requires not just persistence but perseverance. It is rooted in an unrelenting hope and belief in the dignity of all people and how they should be treated. It is rooted in a prophetic call to transform our suffering into advocacy, just as Jesus did.

Extending forgiveness is not easy but with it comes the power to free both the minority and majority cultures from the bondage of their dark past. Many Caucasians have inherited feelings of guilt and shame due to transgressions of their collective history that can cause them to withdraw. Yet as we ethnic minority leaders persist in engaging the majority culture and initiating healthy partnerships, we play a redemptive and prophetic role in encouraging Caucasians to live out who they truly are. This is the beauty of an empowered partnership: neither side is devalued at the others’ expense but both sides are lifted up.

Indeed, there is a beautiful picture of the image of God in Caucasian culture, shrouded by a tainted history and forgotten in the conforming pressures of the “melting pot” of North America. What have we yet to see of the richness of this culture and what it can bring to the diverse mosaic of cultures that God has designed?

As we live out our identity in Christ in the fullness of our respective histories and traditions, we find our place in a story far grander than our mono-cultural history books can record. For God in His wisdom did not allow any one human culture to possess the entire spectrum of His truth and each of our cultures’ stories is an indispensable part of His greater story!

Some of those stories have been forgotten or have gone untold. But God is at work in the world not just in bringing His good news to the unreached but filling in the missing colors of the “unreached” parts of our own hearts. What of His personality and character is waiting to be revealed through cultures we have yet to experience?

Embracing our unique part in God’s story begins with understanding ourselves and the way we relate to others. It requires more than a mental paradigm shift but an expansion of our hearts. It requires a transforming vision of a God more vast and beautiful than we have known, before whom a sea of diverse witnesses will one day gather – clothed distinctly and unashamed in the dignity of their uniqueness.

Moving towards this bigger picture of God starts with each of us. As we envision God’s bigger story and consider the stories of our people yet to be told, we have choices to make about our own. What kind of story do you want yours to be? Will you wait for someone else to write it or will you embrace it as your own?

Pause and Reflect:

- How important is your culture to you? Describe where you are in your journey of cultural awareness.

- What stories or memories from your cultural history have resonated with you?

- How do you think those memories have impacted you or your family and the way you relate to the majority culture today?

- Thinking about your childhood and past, which of the six postures do you relate to the most? Why?

- Consider your friends or colleagues from the majority culture. In what ways can you move towards an equal and empowered partnership with them?

- What barriers stand in the way of this kind of partnership for you?

- Name one way that you see God differently because of your cultural or family background. Name one way that you see God differently because of a culture other than your own.

– Adrian Pei